"Listening DEEP"... Exploring the Elements of Rock Music

My Name is William W. Nelson, and I am the Founder of The Art of Music Sounds Institute (theartofmusicsoundsinstitute.com) is a subsidiary of Classic Rock Turntables.com, Inc. (classicrockturntables.com), a registered NON Profit Corporation of the State of North Carolina.

It is the Mission of the "Intensive Learning" Program at ASMI to teach "Wannabe" Bands how to listen to the Elements of Classic Rock Tracks... By learning the "Art of Listening" to the Sounds they produce, each band will be mentored by a professional Musician to assist them on a path to success!

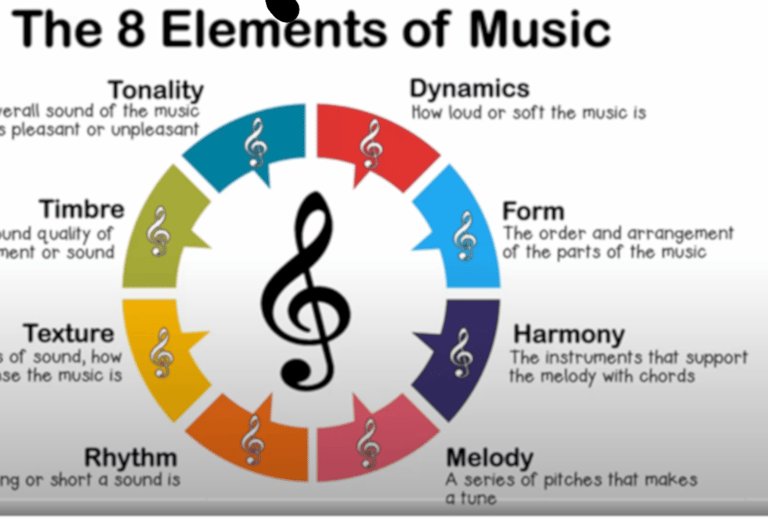

Rhythm: Backbeat Emphasis creates a strong Danceable groove to fundamental Rock

Syncopation: Patterns where Accents fall off of the main Beat with Drum patterns adding interest and drive to Guitar, bass lines, and Vocals

Rhythm Section Layers: Interlocking Patterns that vary in Density and Complexity between Sections

Dynamic Rhythmic Textures: The use of sparser, looser Rhythms for tightly, coordinated, driving Choruses... Bridges or Solos shifts in Meter to heighten Sounds

The ASMI Program:

Our 4-week+ Program (starts the day before the 1st of the Month's Program... 6 Programs per year

Candidates: Through our Interview process, we will select 3 viable Rock Bands who meet the requirements...

Note: extra band Members will be allowed to audit the Program

Assess Musical Proficiency" (technical skills, ensemble playing, , intonation, and expression abilities

Evaluate their Music awareness of the Group, Collaboration, and ability to explore Classic Rock Styles

Consider their Creativity and passion for Classic Rock

Demonstrate their ability to make Cover Tracks of Classic Rock... each band must select 3 tracks to play in the "Band-off" in week 4

Curriculum:

The Evolution of Sound (Weeks 1 & 3)

Phase 1: The Foundations (Early Years – 1955)

"Period Genre Focus Key Listening Elements"

1900 - 1920: proto-Blues... incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the African-American culture that became noticed by early Musicians after the Civil War.

The Proto-Blues "Listening Lab" Elements:

Tracing the transition from a group "shout" to a solo singer responding to their own guitar or banjo line

The 1920s Laboratory: Capturing the "Unwritten."

In the 1920s, the "Art of Listening" underwent a seismic shift, transitioning from an oral tradition to a recorded one. This was the era of "Race Records" and the first commercial capturing of the Delta Blues, and the "Classic Blues" of the vaudeville stage.

Bottleneck/Slide Timbre: Analyzing how early players used metal or glass to mimic the human voice’s ability to slide between pitches (glissando).

Aural Tradition: Understanding music that was never written on a staff, but "etched" into the ear through repetition and variation

Technically, this decade is defined by the Acoustic Recording Process (pre-1925) and the birth of Electrical Recording (post-1925).

In the Acoustic Era (Pre-1925): Musicians played into a large conical horn that physically vibrated a stylus.

Technical Constraint: Bass frequencies were almost impossible to capture, and "loud" instruments like drums would cause the needle to jump.

Listening Lab Focus: We analyze why early 1920s blues sounds are perceived as "thin" and mid-range heavy, and how artists like Blind Lemon Jefferson utilized high-pitched guitar runs to cut through the noise floor.

The Electrical Revolution (1925–1929): The introduction of the Microphone changed the "Art of Music Sounds" forever.

Technical Shift: The microphone allowed for "Intimate Listening." Singers no longer had to shout to be heard by a horn; they could whisper, groan, and use subtle vocal nuances (the "croon").

Theory III Integration: We study the Harmonic Complexity made audible by microphones—hearing the vibrating wooden body of the guitar and the resonance of the room for the first time.

The Emergence of "The 12-Bar Standard."

While Proto-Blues was fluid and "drifting," the 1920s saw the standardization of the 12-Bar Blues Form.

Structural Analysis: We break down the AAB lyric structure (Statement, Repetition, Resolution) and its corresponding chord progression:

Line 1: I - I - I - I (The Setup)Line

Line 2: IV - IV - I - I (The Tension)Line

Line 3: V - IV - I - I (The Resolution/Turnaround)The Lab Task:

Students listen to Bessie Smith (Classic Blues) vs. Charley Patton (Delta Blues). We analyze how the "Professional" vaudeville sound utilized a piano/horn section for strict timing, while the "Country" sound utilized "irregular measures"—where the singer might add a beat or two to a bar based on emotional whim.

The "Cousin of Nashville" Connection

The 1920s also gave us the Bristol Sessions (1927), often called the "Big Bang of Country Music," occurring just across the mountains from Asheville. Here, we see the crossover: the same 12-bar structures and "Blue Notes" used by bluesmen were being adopted by The Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers (The Singing Brakeman), who famously integrated "Blue Yodeling."

To truly understand the "Cousin of Nashville" connection, we have to look at how the 1920s functioned as a massive Cultural Blender. In the Asheville and Appalachian region, the "Art of Music Sounds" was being forged by two distinct but overlapping forces: the Delta/Country Blues and the Early Hillbilly/Country sounds.

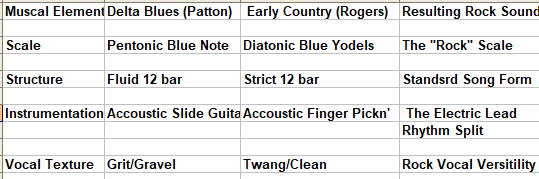

The DNA Comparison: 1920s Roots Lab

We will analyze two seminal 1927-1928 recordings to see where the branches of the "Classic Rock Tree" first began to tangle.

Track A: Charley Patton – "Pony Blues" (1929)

The Sound: Raw, percussive, and rhythmically erratic Delta Blues.

The Laboratory Analysis: Patton uses the guitar as a drum. He hits the body of the guitar to create a "thump" on the downbeat.

Theory III Listening: Notice the Irregular Meter. Patton doesn't play a perfect $4/4$ time. If he needs an extra beat to finish a vocal thought, he adds it. This is "Human Timing" vs. "Metronomic Timing.

"The Technical Element: Patton’s voice is "gravelly" and distorted naturally—the acoustic precursor to the overdriven vocals of 1960s Rock.

Track B: Jimmie Rodgers – "Blue Yodel No. 1 (T for Texas)" (1927)

The Sound: The "Singing Brakeman" blends Swiss yodeling with African American Blues.

The Laboratory Analysis: Rodgers uses a standard 12-bar blues structure ($I-IV-V$), exactly like Patton, but his guitar playing is "cleaner" and uses alternating bass notes (the "boom-chicka" style).

Theory III Listening: Listen for the "Blue Note" yodel. Rodgers takes a traditional European folk technique (the yodel) and applies it to the "Blue" intervals. This is the exact moment "Country" and "Blues" shook hands.

The "Overlapping DNA" Table

1930 - 1939 In the 1930s, the "Art of Music Sounds" underwent a radical transformation driven by two opposite forces: the massive, choreographed power of The Big Band and the haunted, solo intensity of Delta Blues.

During this decade, the Institute’s laboratory focuses on the transition from "Stomp" to "Swing" and the first successful attempts to win the battle against volume through Early Amplification.

1. The Rhythmic Engine: The "Swing Feel."

The most important "Theory III" skill for this decade is distinguishing between a straight beat and a triplet-based swing.

Technical Definition: In the 1930s, the $4/4$ time signature evolved. Instead of four even quarter notes ($1-2-3-4$), musicians began playing with a "long-short" lilt.

The Physics of the Beat: This is technically a twelfth-note feel, where the first note of a pair is twice as long as the second.

The Lab Task: We compare a 1920s "March-style" folk song to a 1930s Benny Goodman or Count Basie track. Students must "feel" the skip in the rhythm—the heartbeat of what would eventually become the Rock 'n' Roll shuffle

2. The Texture Lab: Brass vs. Reeds

The 1930s Big Band era was a masterclass in Tone Color (Timbre).

Brass (Trumpets/Trombones): Sharp, directional, and "bright." We analyze how brass hits were used as "punctuation" in a song.

Reeds (Saxophones/Clarinets): Warm, "woody," and capable of smooth, vocal-like slurs.

The Evolution: We track how the "Screaming Lead Trumpet" of the 30s eventually became the blueprint for the "Screaming Lead Guitar" of the 70s. Both occupy the same frequency range and perform the same "soloist" role.

3. The Birth of the Electric Sound (1931–1939)

This is the "Holy Grail" moment for the Institute. Before 1931, the guitar was a rhythm instrument, buried by the loud brass sections.

The "Frying Pan": In 1931, the Rickenbacker "Frying Pan" (lap steel) introduced the first Electromagnetic Pickup.

The Theory of Transduction: We study how a vibrating string disrupts a magnetic field to create an electrical signal. This changed the "Art of Listening" from hearing moving air to hearing moving electrons.

Charlie Christian: We analyze his 1939 recordings with Benny Goodman. For the first time, a guitar could play single-note lines as loud as a saxophone. The "Lead Guitarist" was born.

4. Delta Blues: The Peak of the Acoustic Soloist

While cities were swinging, the Delta was producing its most sophisticated acoustic sounds.

Robert Johnson (1936-37): We analyze Johnson’s "Cross Road Blues."

Theory III Integration: We look at his Complex Fingerpicking. He plays the bass line, the chords, and the lead melody simultaneously. This "One-Man Band" approach is the DNA for the "Power Trio" format (Cream, Jimi Hendrix Experience) of the 1960s.

Institute Pondering Point: "The Volume War"

The 1930s teach us that technology follows the artist's need. Big Bands got bigger to fill larger dance halls; guitars got electrified to be heard over the Big Bands. The "Sound" of Rock was an inevitable result of musicians wanting to be louder and clearer.

1940 - 1949 The Lineage of Loud: A Century of Musical Evolution

In the 1940s, the "laboratory" of music began to boil. The smooth, disciplined "Swing" of the 1930s fractured into two radical directions: the high-speed intellectualism of Be-Bop and the high-energy, dance-driven pulse of Jump Blues.

1. The Jump Blues Explosion: Rock’s Direct Ancestor

As the Big Bands became too expensive to tour during WWII, smaller "combos" took over. They kept the horn section but stripped it down to a few saxophones and a hard-driving rhythm section.

The "Shuffle" and Increased Tempo: Jump Blues (Louis Jordan, Big Joe Turner) took the 1930s swing and sped it up. The "relaxed" lilt became a "driving" force.

The Laboratory Focus: We analyze Volume and Energy. This music was designed for "juke joints"—it was loud, rowdy, and emphasized the "Backbeat" (the snare on 2 and 4), which is the literal heartbeat of every Rock song.

2. The Walking Bass Line: The "Engine" of the 40s

One of the most critical Theory III: Listening skills for this decade is identifying the Walking Bass.

Technical Definition: Instead of just playing on beats 1 and 3, the bassist plays steady quarter notes that "walk" up and down the scale, connecting the chords.

The Impact: This created a sense of forward motion. In the Lab, we trace how this upright bass "walk" eventually transitioned to the electric bass "riff" in the 1950s and 60s

3. Be-Bop: The Intellectual "Sound Laboratory."

While Jump Blues was for the feet, Be-Bop (Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie) was for the head.

Complex Harmony: Be-Bop introduced "extended" chords (9ths, 11ths, 13ths) and rapid-fire key changes.

The "Art of Listening": We train students to hear "dissonance." Be-Bop musicians deliberately played "outside" the key to create tension—a technique later used by psychedelic rock and heavy metal guitarists.

4. The Electric Guitar Transition (The Charlie Christian Legacy)

Charlie Christian didn't just plug in; he changed the language of the instrument.

From Rhythm to Horn-Like Lines: Christian treated the guitar like a saxophone. He played long, fluid, melodic lines that spanned several octaves.

The Laboratory Focus: We listen for Sustain. Because the guitar was amplified, notes could ring out longer than they could on an acoustic. This is the first step toward the "feedback" and "infinite sustain" of 1960s Classic Rock.

5. The "Cousin of Nashville" Moment: Honky Tonk

Parallel to Jump Blues and Be-Bop, the 1940s saw the rise of Honky Tonk in Country music (Hank Williams).

The Intersection: Honky Tonk introduced the "Pedal Steel" and the "Fiddle" as lead instruments, often using the same "swing" feel found in Jump Blues.

Institute Pondering Point: We observe how the "Grit" of Jump Blues and the "Twang" of Honky Tonk were moving closer and closer together, preparing to collide in the early 1950s.

Institute Lab Activity: "The Pulse Test"

We play three tracks from the 1940s: a Be-Bop track, a Jump Blues track, and a Honky Tonk track.

The Task: Students must identify the "Walking Bass" in each and determine which one has the strongest "Backbeat." This identifies the "Rock Potential" of each genre.

Phase 2: The Rock Revolution (1955 – 1969)

Focus: How technology and social change electrified the sound.

The "Listening" Methodology: Music Theory III "Listening"

Level 1: Structural Listening (Identifying the "Skeleton")

Where are the transitions? Is there a bridge or a re-intro?

Level 2: Harmonic Dictation (Identifying the "Muscle")

Is that a bV II chord or a IV chord? Is the bass playing the root or an inversion?

Level 3: Narrative Listening (Identifying the "Soul")

How does the theory (e.g., a sudden key change) support the emotional story of the lyrics?

1955 - 1963 The Crossover

The Institute’s laboratory examines the literal "chemical reaction" that occurred when independent regional sounds—specifically the Country "Twang" of the South and the R&B "Drive" of the urban centers—collided on the national airwaves. This period is less about the invention of new notes and more about the re-packaging of energy.

1. The "Twang" vs. The "Drive"

To understand this era, students must use their Theory III: Listening skills to separate the two primary ingredients of the early Rock 'n' Roll "Sound."

The Country "Twang": Derived from the "Cousin of Nashville" lineage. We listen for the major-key brightness, the "slapback" echo on vocals (Sun Records style), and the "tic-tac" bass (doubling the bass line on a muted guitar).

The R&B "Drive": Derived from the Jump Blues of the 1940s. We analyze the heavy backbeat (snare on 2 and 4) and the aggressive "shouting" vocal style that pushed the limits of early microphones.

2. Lab: The Rise of the "Cover" and "Crossover" Track

We analyze the 1950s industry practice of "covering" songs to move them from the R&B charts to the Pop charts.

The Case Study: We listen to Big Mama Thornton’s original "Hound Dog" (1952) and compare it to Elvis Presley’s version (1956).

Listening Lab Focus: We identify what was "lost" and "gained." Thornton’s version is a mid-tempo, gritty blues; Elvis’s version is a high-speed, "straight-eighth" rock anthem. This shows how a Crossover Track often simplified the rhythm to increase the "danceability" for a mass audience.

3. Lab: Chuck Berry’s Guitar Patterns vs. Traditional Blues

If the 1940s was about the walking bass, the 1950s was about the Guitar Riff.

The Traditional Blues Shuffle: We listen to a 1930s Delta shuffle where the rhythm is "swung" (triplet-based).

The Berry Shift: We analyze Chuck Berry’s "Johnny B. Goode." Students observe how he took the Boogie-Woogie piano left-hand pattern and moved it to the low strings of the electric guitar, playing it with a straight-eighth feel.

The "Double Stop": We study Berry’s signature move—playing two notes at once (usually on the top strings) to create a "horn-like" blast. This is the moment the guitar officially replaced the saxophone as the "voice" of the band.

4. The "In-Between" Years: 1959–1963

Before the British Invasion, Rock 'n' Roll underwent a "polishing" phase.

The Wall of Sound: We analyze Phil Spector’s production. This is an early Theory III lesson in "Mono-layering"—doubling and tripling instruments (three pianos, five guitars) to create a massive, orchestral sound on a single radio speaker.

The Surf Sound: Tracing the evolution of "clean" electric guitar through Dick Dale and The Beach Boys, focusing on "tremolo" and "spring reverb" as new sonic colors.

Institute Pondering Point: The "Hybrid" Identity

This era proves that Rock 'n' Roll was not a single genre, but a Radio Phenomenon. It was the first time in history that a teenager in Asheville could hear the same sound as a teenager in Detroit. The "Crossover" wasn't just musical; it was the beginning of a unified youth culture.

1964–1969: The British Invasion to Woodstock

At the Institute, we analyze this period through the lens of "The Cultural Return": how British kids took American R&B, Blues, and Rockabilly (which had become "sanitized" or forgotten in the US by the early '60s), electrified it, and sold it back to America with a new, sophisticated edge.

1. The Musical Shift: From "The Single" to "The Sound"

Before 1964, the US charts were dominated by solo pop singers and novelty acts. The British Invasion shifted the focus to the self-contained band—groups that wrote their own material, played their own instruments, and created a cohesive sonic identity.

Harmonic Innovation: Moving beyond the standard I-IV-V blues progression. We analyze how The Beatles used "Picardy Thirds" and modal shifts borrowed from English Folk and Classical music.

The "Dirty" Tone: The Kinks and The Who introduced deliberate distortion (Dave Davies famously sliced his amp speaker with a razor for "You Really Got Me"). This is the birth of the Hard Rock "Laboratory.

The Riff as Foundation: Instead of just strumming chords, bands like The Rolling Stones and The Animals built songs around repetitive, melodic guitar "hooks" (riffs), a direct evolution from Delta Blues.

In this "Evolution Lab," we witness the fastest rate of change in musical history. In just five years, the music moved from the basement clubs of Hamburg to the sophisticated, multi-track experiments of Abbey Road, and finally to the massive, mud-soaked stages of Woodstock.

1. 1964–1965: The Beat Era

Focus: Energy, Synchronicity, and the "Mop-Top" Pop Sound. During these two years, the British Invasion bands (The Beatles, The Hollies, The Searchers) focused on refining the "Combo" sound.

The Vocal "Blend": We analyze the move from a single lead singer to three-part vocal harmonies. We study the influence of the Everly Brothers and Motown on British vocal arrangements.

The "Jangle": Technical analysis of the Rickenbacker 12-string guitar. Students listen for the "chime" and "shimmer" (high-frequency resonance) that defined the mid-60s pop sound.

Theory III Tip: Identify the V-IV-I cadence and the "Major II" chord (e.g., a D Major chord in the key of C), which gave British pop its distinct, bright lift.

2. 1966–1967: The Experimental Turn

Focus: The Studio as an Instrument. This is where Music Theory III truly takes center stage. The laboratory moves away from what a band can play live to what can be created through technology.

The Sitar and Indian Ragas: We study "Within You Without You" and "Fancy." We analyze the Drone (static harmony) and the use of the Mixolydian mode, breaking away from Western blues-based structures.

Tape Manipulation: We analyze ADT (Artificial Double Tracking) and "backwards" tracks. Students learn to hear the "attack" and "decay" of a note in reverse—a sound that defines Psych-Rock.

Non-Standard Song Structures: We move beyond Verse-Chorus to Linear Song Forms (songs that don't repeat, like "A Day in the Life" or "Happiness is a Warm Gun").

Lab Activity: The Five-Year Transformation

3. 1968–1969: The Heavy Turn

Focus: Saturation, Sustained Distortion, and the Rise of the "Power Trio." As the decade closed, the "clean" pop of the mid-60s was replaced by a grittier, louder, and more aggressive sound.

The Yardbirds to Zeppelin: We analyze the transition from the blues-rock "rave-ups" of The Yardbirds to the "Heavy" Blues of Led Zeppelin. We study the use of unison riffs between the guitar and bass to create a "wall of sound."

The Gritty "White Album": We contrast the polished production of Sgt. Pepper with the raw, "live" feel of The Beatles (White Album). We listen for "Helter Skelter" as a precursor to Heavy Metal.

Woodstock '69 Impact: We analyze how the need to play for 400,000 people led to the development of the high-wattage Marshall stack and long-form improvisation.

The "Amplified" Message: Woodstock proved that Rock could be a vehicle for social and political change (e.g., Country Joe McDonald or Jimi Hendrix’s "Star Spangled Banner").

Scale and Scope: It shifted the "Laboratory" from the recording studio to the massive outdoor arena. This required a new type of performance—longer improvisations (The Who, Santana, Ten Years After) and more powerful PA systems.

The Fragmentation: Immediately after Woodstock, we see the "Invasion" splinter into dozens of subgenres: Prog Rock, Heavy Metal, and Singer-Songwriter.

We start by analyzing and comparing Bands (The Beatles and The Rolling Stones) and listen to Tracks from '64, '66, and '69... and many more.

"Listen to The Isley Brothers' version of 'Twist and Shout' (1962) and The Beatles' version (1963). Identify three 'British' elements—vocal grit, tempo, or instrumentation—that changed the sound for the American ear.

· Listen to the Covers of Rock Tracks from 50s on... Blues Rock, Folk Rock, and Country Rock as Sounds have evolved.

The Task: Using Theory III skills, identify one technological change (e.g., more reverb, more tracks) and one harmonic change (e.g., more complex chords, more "dissonance") in each transition.

Now, we enter what many consider the "High Art" period of Rock. This is where the Institute’s laboratory moves from the garage to the multi-track recording studio. The focus shifts from "playing a set" to "creating a world."

1970–1975: The Rise of the Album & The Sonic Architect

During this window, the Long Play (LP) record replaced the 45rpm single as the primary medium of artistic expression. For your Rock Bands and listeners, this era is about Symphonic Thinking—the idea that a song is part of a larger structural whole.

The "High Art" period of Rock Sounds.

This is where the Institute’s laboratory moves from the garage to the multi-track recording studio. The focus shifts from "playing a set" to "creating a world. During this window, the Long Play (LP) record replaced the 45rpm single as the primary medium of artistic expression. For your Rock Bands and listeners, this era is about Symphonic Thinking—the idea that a song is part of a larger structural whole.

1. High-Fidelity (Hi-Fi) Production

By 1970, 16-track (and eventually 24-track) recording became the standard. This allowed for "layering" that was previously impossible.

The Laboratory Focus: We analyze the "Stereo Field." Students learn to hear where instruments are placed in the 3D space of a mix—far left, far right, or "center stage.The "Clean' Revolution": We contrast the "dirty" garage sounds of the late 60s with the crystal-clear, polished production of bands like Steely Dan or Fleetwood Mac.

2. The Shift to "Sonic Architects

"In this era, the producer and the engineer became as important as the lead singer. The band members became "architects" building massive soundscapes.

Led Zeppelin (The Architect of Power): We study Jimmy Page’s use of ambient miking. Instead of putting a mic right against the drum, he put it in a hallway to capture the "room sound" (e.g., "When the Levee Breaks").

Pink Floyd (The Architect of Space): We analyze The Dark Side of the Moon as a masterclass in Music Theory III: Listening. Students identify non-musical sounds (clocks, heartbeats, cash registers) used as rhythmic and melodic elements.

3. The Concept Album & Large-Scale Form

This is where the Institute explores how Rock borrowed from Classical Music.

Theme and Variation: Just as a symphony has a recurring theme, concept albums use "leitmotifs"—musical phrases that reappear in different songs to tell a story.

The Suite: We analyze tracks like "Close to the Edge" (Yes) or "Stairway to Heaven," looking at how they move through "movements" rather than just Verse-Chorus-Verse.

4. Subgenre Explosion: The Branching of the Tree

Between '70 and '75, the "Rock" trunk of the tree split into distinct identities that your bands will study:

Prog Rock: High technical virtuosity, odd time signatures (7/8, 11/8), and fantasy/philosophical themes.

Glam Rock: The "Art School" influence—focusing on performance art, fashion, and theatricality (David Bowie, T-Rex).

Heavy Metal: The "Tritone" ($b5$ interval). We study how Black Sabbath used "The Devil’s Interval" to create a darker, heavier harmonic language.

1976–1984: The Great Reaction (Punk vs. New Wave)

If 1970–1975 was about "The Architect," this era is about The Rebel and The Stylist.

1. The Punk Reset: "Three Chords and the Truth... "By 1976, Rock had become complex and expensive. Punk was the "stripped down" response.

· The Laboratory Focus: We analyze the Economy of Sound. How do The Ramones or The Sex Pistols create maximum impact with minimal harmonic movement?

· Theory Integration: We study the "Power Chord" ($1 - 5 - 8$) and why it became the essential building block for Rock bands, removing the "clutter" of 3rds to allow for high-volume distortion.

2. The New Wave & The Synthesizer:

· As Punk evolved, it met technology. This gave birth to New Wave, where the "Sonic Architect" returned, but with a keyboard instead of a guitar.

· The "Digital" Ear: We listen to the shift from Analog (warm, drifting) to Digital (precise, cold) oscillators.

Layering Textures: Analyzing how bands like The Cars or Talking Heads blended traditional Rock instruments with sequencers and drum machines.

1984–1990: The Digital Frontier

This is the era where the "Sound" of music changed more than the "Songs." This is the peak of Production & Fidelity study. This is considered the end of the Era of "Classic Rock."

1. The MIDI Revolution:

1983-84 saw the birth of MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface). For the first time, instruments could "talk" to each other.

The Impact:

We analyze how this allowed for "Perfect" timing. We contrast the "human swing" of a 1971 Led Zeppelin track with the "grid-locked" precision of a 1985 synth-pop track.

2. The "Big 80s" Sound: Digital Reverb & Gated Drums

Perhaps the most recognizable "Sound Evolution" in history.

The Gated Snare: We study the "Phil Collins" drum sound. We use our Theory III: Listening skills to identify the "envelope" of a sound—how digital reverb is cut off abruptly to create a "gated" explosion.

FM Synthesis: Listening for the "glassy" bells and "slap" basses of the Yamaha DX7, which defined the hits of 1984–1987.

3. Arena Rock: The Wall of Sound 2.0

Bands like U2, Van Halen, and Def Leppard used this technology to make Rock sound massive enough to fill stadiums.

The Laboratory Focus: We analyze "Sonic Depth." How do delays and chorusing effects make one guitar sound like an orchestra?

Subgenre Explosion: This period gives us Hair Metal, Gothic Rock, and Thrash Metal. We track how Metallica took the "speed" of Punk and the "complexity" of 70s Prog to create a new subgenre.

Institute Lab Activity: "The 80s Transformation"

We take a simple 12-bar blues progression (from the 1930s lesson) and "re-produce" it three times in the lab:

Punk Style: Three chords, high gain, no effects.

New Wave Style: Add a synthesizer hook and a "driving" straight-8th note bass line.

Digital Frontier Style: Add gated reverb to the snare and a digital delay to the guitar.

Outcome: Students realize that while the "Music Theory" (the chords) remains the same, the "Sound Art" (the production) alters the entire emotional meaning of the song.

Moving into the 1990s, the Institute's "Laboratory" observes a fascinating phenomenon: The "Great Regression." After a decade of digital perfection and MIDI-controlled precision, the musical world pivoted back to the "honest" sounds of the early days, but with a new layer of angst and distortion.

The Decade 1990s: The Grunge Reset & The Analog Revival

Focus: Authenticity, Lo-Fi textures, and the "Unplugged" movement.

1. The Rejection of "The Grid"

In the late 80s, everything was perfectly on time (MIDI) and perfectly polished. Grunge (Seattle) and the Alt-Rock movement were a direct reaction against that "fake" sound.

The Sound of "Dirt": We analyze the return to fuzz and feedback. Instead of the "glassy" 80s digital delay, bands like Nirvana and Soundgarden used analog pedals that sounded "broken" and "thick."

Dynamic Range: We study the "Loud-Quiet-Loud" formula. This is a core Theory III: Listening skill—identifying how a band uses a "hollow" verse to set up a "saturated" chorus.

2. The Unplugged Movement

This decade saw a massive return to the "Folk/Blues" roots through MTV Unplugged sessions.

Laboratory Focus: We strip back the 80s production to see if the "Songs" still stand. We compare Eric Clapton’s 1970s electric work with his 1990s acoustic performance to study Timbre (Wood vs. Wire).

The Decade 2000s: The Digital Democracy

Focus: The Napster Effect, Home Studios, and Garage Rock Revival.

1. DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) Culture

The lab shifts from million-dollar studios to the laptop. Software like Pro Tools and Logic allowed bands to record in their basements.

The "Indie" Sound: We analyze how "Lower Fidelity" became a choice. Bands like The Strokes or The White Stripes deliberately tried to sound like they were recorded in the 1950s—completing the "Evolution Circle."

2. The Return of the Riff

After the abstract sounds of the late 90s, the 2000s saw a "Classic Rock" revival.

Theory Integration: We trace how 2000s bands borrowed the "British Invasion" blueprints (Weeks 1 & 2) and updated them with modern energy.

2010 - 2025: The "Hybrid Era"

Focus: Genre-Blurring and the "Producer as Artist."

1. Spatial/Immersive Audio (Dolby Atmos)

The most significant shift in listening since Stereo.

Theory III Goal: We learn to "place" sounds above, behind, and around us. Music is no longer a "wall"; it’s an "environment."

The "Viral" Structure: Analyzing how TikTok changed song architecture—the "hook" now often comes in the first 5 seconds.

2. The AI & "New Heritage" Paradox

While AI can generate "Music Sounds," the Institute focuses on the Human Element.

Current Trend: We analyze the "New Heritage" movement—artists like Greta Van Fleet or Chris Stapleton who are "mining the archive" of the 1930s-1970s to create something that feels "real" in a digital world.

Final Lab Project: "The Full Circle"

The Bands' final task is to take a 2024 track and "De-Evolve" it.

Task: Identify the 2020s production (spatial audio), the 1990s attitude (grunge distortion), the 1970s structure (concept/long-form), and the 1930s DNA (Blues/Gospel scale).

The Final Week... Practice. Practice, Practice... the Band Off"

The mentor’s job in the final week is to shape each band’s one‑hour show into a tight, confident, entertaining set that feels ready for a real venue and a live‑streamed “Band Off” with audience voting, American Idol–style. Below is a compact checklist of what that mentor will ponder and actively assess.

1. Big‑picture readiness

Clarity of the band’s identity: genre center of gravity, visual vibe, and how the three chosen classic rock songs fit that story across a one‑hour set.

One‑hour set architecture: opening impact, mid‑set pacing, and closing “signature” tune; smooth emotional and tempo arcs rather than a random song pile.

Rehearsal goals for the week: 2–3 non‑negotiables (tight endings, solid vocals, gear reliability) agreed with the band on Day 1 of final week.

2. Song performance details

For each of the three “Band Off” songs and the rest of the set:

Note and rhythm accuracy: correct chords, riffs, bass lines, drum grooves, and form; no train‑wrecks on intros, bridges, or endings.

Tone and blend: guitar/bass/drums/keys/vocals balanced so that nothing masks the lead vocal or key hooks; no harsh or thin tone that distracts.

Dynamics and articulation: use of soft/loud sections, builds, hits, and stops; accents and grooves feel authentic to the classic rock style chosen.

3. Ensemble tightness and communication

Time and togetherness: band locks to a common pulse, especially on transitions, fills, breaks, and endings; drummer and bassist function as a solid core.

Cues and eye contact: clear non‑verbal leadership for starts, stops, modulations, and “extend the vamp” moments; everyone actually looking up, not glued to the floor.

Recovery skills: how they handle mistakes—staying in form, not stopping mid‑song, using band communication to land together.

4. Stagecraft and audience connection

This is crucial because of the live venue plus YouTube audience and voting.

Stage presence: posture, movement, and facial expression that match the energy of the song; performers do not look bored, scared, or apologetic.

Audience engagement plan: who speaks to the crowd, what they say between songs, and how they briefly frame each key tune without rambling.

Camera awareness: basic understanding of where cameras are, avoiding dead angles and clutter; simple choreography so shots look active on the stream.

5. “Band Off” structure and voting flow

Pre‑Band‑Off day: a full‑length run‑through of the one‑hour set under “show conditions” (no stopping), timed and critiqued, then a second focused pass on problem spots.

Live competition format:

All bands perform their one‑hour set (or a defined showcase portion) before elimination.

Audience voting window opens during/just after each performance via YouTube tools (likes, pinned poll, or off‑platform link), with a clear cut‑off time, avoiding confusion seen in some multi‑platform TV formats.

Lowest‑voted act is eliminated; the final two return for a “3‑song showdown,” ideally their sharpest classic rock pieces or one “signature,” one ballad, one high‑energy closer.

6. Mentor’s daily focus during final week

Early‑week (Mon–Tue): locking arrangements, forms, and critical transitions; confirming keys, tempos, and song order for the one‑hour show.

Mid‑week (Wed–Thu): polishing tone, dynamics, backing vocals, and count‑offs; building endurance so players can deliver strong for a full hour.

Day‑before and day‑of: full show run, micro‑tweaks to pacing, and mental prep; emphasizing confidence, professionalism, and band unity on stage.